At the Pacific Coast Region (NMRA) convention last weekend, I picked up a really old Silver Streak car kit. I suspect it predates 1953, since lists of Silver Streak freight car models for that and all subsequent years don’t contain it. (My source for this kind of info is, as usual, the HOSeeker website, at: https://hoseeker.net/truscalesilverstreak.html .)

Supporting that idea of kit age is the car kit box, black with silver decoration. Note below, that on the top of the box is shown what was probably Silver Streak’s best-known and certainly best-selling model, the Hart convertible gondola. At this time, the company name was “Pacific HO,” thus the PHO reporting marks on the gondola on the box.

This is the earliest box used by Silver Streak. The same company made Tru-Scale roadbed, which became a big enough seller that the company changed its name from Pacific HO to Tru-Scale, and also changed the box for car kits to a greenish color.

Eventually the original company went out of business, and for a time Walthers sold the car kits, using a similar box but in yellow, and with the Walthers name replacing that of Tru-Scale.

The car that I acquired had been partly assembled, with the basic wooden body box very nicely built, the underframe mostly completed except for couplers, and the printed sides attached. As mentioned, I have not found any Silver Streak product list that shows this URTX scheme, confirming the early date. It’s also interesting that the model is 40 scale feet long. Many early Silver Streak models were about 10 percent oversize, but not this one.

There were essentially all the needed parts still in the kit box. The photo below shows them (you can click on the image to enlarge it if you wish). The end and roof “wood” sheathing is at bottom, and the rather wide running board at left.Next to the running board at the top are the dummy couplers (their boxes are near the end parts), and next to the couplers are the ice hatches. Note that these have the long boards to support hatch rests, but no ice hatch platforms, as was usual on wood roofs. I have not found other Silver Streak reefer kits with wood roofs and such ice hatches.

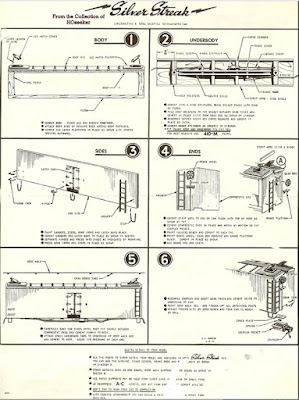

My kit box didn’t contain any instructions. Instructions for later Silver Streak refrigerator car models are available on the HOSeeker website, as I show below, but obviously a different car is shown in this document, representing a metal instead of wood roof, and with ice hatch platforms. I will use these directions to the extent that they apply.

I want to proceed to complete this model, using the major kit parts, but upgrading a number of the minor parts such as grab irons and ladders, and of course couplers. I also want to examine what I can find about the prototype for this car (in the 1950s, it was not yet the practice to decorate models for prototypes that never had that body type). I will describe those processes in a future post.

Tony Thompson