I know from many conversations in the corridors at modeling meets that modelers tend to view waybills as simple and straightforward documents. Of course, some examples are exactly that. But many are not, and the subtleties are endless. I thought it might be interesting to consider some examples of the various complexities that sometimes arose.

For the present post, let me choose an example that relates to routing. Modelers often assume that an originating railroad would naturally route loads as far as possible on its own rails, and when free to do so, they would indeed do that; but shippers had the absolute right to choose routing, and normally did so. Yet routings can be head-scratchers, whoever chose them. The example for today is a Frisco waybill I was given some time ago, darkened with age. (Feel free to click on the image to enlarge it, if you wish.)

Let's look at the routing. In the upper left column of the bill, you will note that it states the routing as “FRISCO CBQ CMSTP&P NKP DLW BM” in moving this load of lumber from Birmingham, Alabama to Mountainview, New Hampshire. Junctions are not listed, though the form clearly states, “Show each junction . . .” The yard stamps at the bottom show what actually happened, and when. Note that stamp colors vary from black and purple to blue.

The waybill is dated May 19, 1950, normally the day (possibly the day

before) the load is to be picked up, in SOU 11836, a 1937 AAR box car of

40-ton capacity. The first stamp at lower left indeed shows the car

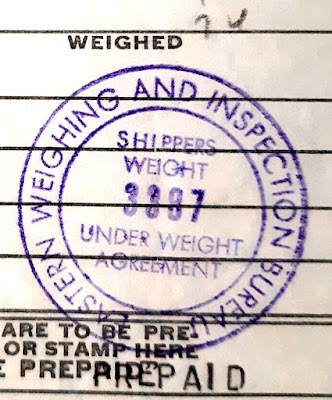

received in the yard at Birmingham on May 20. The car was not weighed,

however, until May 22, as the white scale slip (pasted on) tells us,

with a cargo weight of 54,300 pounds (the waybill itself states 50,000

pounds, likely an estimate at time of loading).

The second yard stamp is from the Burlington at St. Louis on May 23, and right above it is another Burlington stamp, for Willis Yard at Galesburg (Illinois) on May 25. Then the car was interchanged at East Moline (note handwriting above routing list) with Milwaukee Road, then entered the Chicago area. The next stamp is a Milwaukee stamp, showing the car received at Bensenville, Illinois on May 27.

Note on the waybill that “Cheneyville” has been handwritten in the routing area, and indeed, that occurred, a transfer from the Milwaukee to the Nickel Plate at Cheneyville, Illinois on May 28. The next stamp, on May 30, shows the transfer from the NKP to the DL&W, though a location isn’t given. Presumably it was Buffalo, New York, the only interchange point between the two roads that is listed in the Official Railway Equipment Register (ORER) in 1950.

The Lackawanna transferred the car to the Delaware & Hudson at some point (though that isn’t in the original routing), evidently at Binghampton, New York. Note the stamp in the upper center of the waybill, mentioning this routing change. The car arrived at Mechanicville, New York on May 31. It was then transferred to the Boston & Maine that same day, and arrived on June 1 in Mountainview, NH, on the far eastern edge of New Hampshire.

It’s a roundabout trip, no question, and one might wonder why that happened. Birmingham was the easternmost point on the Frisco, and they moved the car as far north as they could, to St. Louis. From there, however, it’s murky. If you were going to use the Nickel Plate anyway, why not route directly to Buffalo from St. Louis? Shorter, and certainly faster than routing through the congestion of Chicago, then coming back south to Cheneyville. Or for that matter, why not transfer to the Nickel Plate in Chicago?

And the routing could have been even simpler. From either Chicago or Buffalo, the New York Central’s water-level route seems an obvious eastward choice, and the Central could even have been selected all the way from St. Louis to the interchange with the final railroad, Boston & Maine, at Troy, New York.

So, a complex routing and thereby an interesting waybill. But what’s the point? First, this example shows how much information can be deciphered from a waybill after it reaches destination. Second, the complex and somewhat roundabout routing reminds us that the obvious and direct route is most certainly not always used. (Though in this case, it could be argued that north from Birmingham to Chicago, then eastward to New Hampshire is at least approximately always in the right direction.) I have seen less direct routings in some cases.

Model waybills normally are not prepared with yard stamps, so all these details would not be possible to reproduce in most model situations. But the scale weighing slip and a few of the stamps in the middle of the bill could certainly be reproduced. This particular bill doesn’t carry many hand-written remarks, but some bills are covered with them. These are easily added to a model bill. Whichever features one might choose to reproduce in model form, the goal is a more realistic model waybill.

Tony Thompson