For decades, prototype railroads have used a paper form intended to route a damaged car to its home shop for repairs. Usually of a size to be stapled to a route card board, they were usually light card stock. I thought this might be a good form to introduce on my layout.

(For background on route card boards, you might wish to look at this post: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2011/11/chalk-marks-and-route-cards.html , with more information on the actual AAR standards for such boards described at this link: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2011/12/route-cards-6.html .)

Here’s a Southern Pacific example of such a Home Shop form, well darkened by being out in the sun and weather until I rescued it from a car body with no trucks (thus probably no longer headed somewhere). The original is 3.25 x 7 inches in size.

The back of this card is interesting: it can serve to direct a car’s location in a train, for example a very light car might well be handled preferentially at the rear of the train. I will have to give some thought to whether I can use this in model form.

The card is a little damaged and quite dark in color. But of course in Photoshop all that is fixable. I lightened the background, removed the pencil writing, and repaired a few damaged areas. This gave me a starting point I could use.

Next I removed the part of the image that wouldn’t fit with my era, namely the four railroads listed at the top of the form (SP, SSW, NWP, SDAE). I then sized the image so it would fit into my waybill sleeves, which are baseball-card-collector sleeves, with a long dimension of 3.5 inches. This could now be printed out for use in an operating session.

To illustrate, here’s a yellow Empty Car Bill, overlaid with a filled-out Home Shop card. This doesn’t change how the car will be handled in my operating session, but it makes a different direction being given to the crew. The variety seems like a good feature. On some layouts, with foreign-road interchanges, or with main yards that direct empties for loading, this could change car handling.

I filled this out in ink for visibility, but most prototype examples I have seen were filled out in pencil. I will experiment with a soft pencil to see if that can be more visible. The prototype form is over twice as big and so writing is easier to read on it.

I should mention here that I do have a prototype SP bad-order card in use on the layout, as I have described previously (you can see my post about it at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2018/04/a-new-bad-order-card.html ). But because it is “nice looking,” as one person put it, visiting operators don’t like to use it to designate cars that need work. I like the “Home Shop” card because it can be used to move cars or to indicate bad orders.

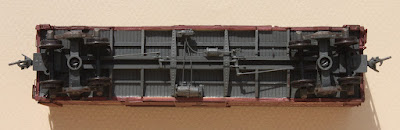

I should also show an example of a Home Shop card from another railroad, in this case Santa Fe. I found this on a car not at Stockton, as the card mentions, so either the car was continuing to be moved, or had been repaired and the card not removed. This card is 8.75 x 3.75 inches in size.

The back is quite interesting; it is a Bad Order card, so obviously a carman could use whichever side suited his needs. It calls for quite a few specific indications of why the car is bad-ordered, and is of course a rather eye-catching color (the original is more of a fluorescent orange).

I will return to the topic of ways such cards could be used in model layout operation, along with results of my own experiments, in a future post.

Tony Thompson