In my layout operating sessions, I usually operate either a section of the Coast Division mail train, or a deadhead move of passenger equipment, as one of several through trains on the Southern Pacific main line. I like to vary the equipment in these consists, but not particularly being a passenger modeler, I sometimes find myself without many options. Accordingly, I have gradually accumulated some stand-in cars which look all right among their “betters.”

One of these is a converted wartime military Pullman, modified to a baggage-express configuration, as was done by a number of railroads. It’s a model I inherited from my good friend, the late Richard Hendrickson (see my remembrance at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2014/07/in-memoriam-richard-hendrickson.html ), lettered for the Burlington.

He modeled October of 1947, and at that time, the model’s Allied Full-Cushion trucks would still have been in service. But by my modeling year of 1953, these would have been gone. I nevertheless operate the car occasionally, just as Richard modeled it. It isn’t a stand-in for model accuracy (except for trucks), but is perhaps unlikely on the SP Coast Route, presumably representing a through load of mail or express.

An RPO car is a natural in a mail train. I have a brass RPO, correct for SP, though its trucks roll so poorly that I dislike operating it. I could of course replace the trucks. But I have an alternative. Years ago, I bought one of the Rivarossi heavyweight RPO models (described by the importer, AHM, as a “1920 Baggage P.O.”), which was lettered for Santa Fe.

Now it was unusual for RPO cars other than than the home railroad to be seen in trains, so I simply relettered it for Southern Pacific. Its clerestory roof would make it an unusual car in the SP fleet, but there were a few, so I chose a number near the car numbers of similar SP cars. I relied on the information in the excellent reference source, the book “Head-End Equipment,” Volume 3 in the series

Southern Pacific Passenger Cars (SPH&TS, 2007). But it’s definitely a stand-in, not accurately representing any SP car.

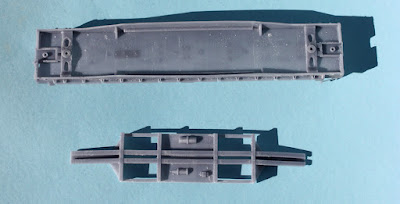

Still another car in the stand-in category is Rapido’s recent Dark Olive Green

car, representing one of the Class B-50-15 box cars converted to head-end

express box car service (AAR type BX). It was shown in my post about

paint schemes as SP 9008, a 1936 conversion which returned to freight

service in 1943 (here’s a link: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2023/08/the-rapido-sp-box-cars-models.html ).

All

472 of the SP 9000-series cars, both BX cars and “Overnight” cars, were

renumbered in the early days of World War II when special freight

services were cancelled nationwide. Among those were 99 head-end cars

renumbered to the 5800 or 5900 series, as shown in detail in Chapter 18

of Volume 3 in the SPH&TS passenger series, mentioned two paragraphs above.

As passenger traffic declined after the war, SP decided around the end of 1948 that these B-50-15 and -16 BX cars were no longer needed in head-end service, and all were either retired or returned to freight service by the spring of 1949, in boxcar-red paint and with their original numbers. (I know this from the SP Car Ledgers, now at CSRM.) Since I model 1953, strictly this would rule out using one of these cars on my layout.

But since I have the model, I

decided to treat it as an unexpected hold-over and give it one of the

5800-series numbers. From the SPH&TS book, I chose one of the

numbers in the group of BX cars assigned to the Northwestern Pacific,

and knew I could use Dulux Gold car numbers from the very nice Thin Film

decal set, HO 160. First, I painted out the original car number, 9008,

using Star Brand Dark Olive Green (STR-29), as you see below; then I painted out most of the other small lettering on the side.

But the car remains an anomaly historically, so the car will definitely be a stand-in. I have weathered it to get a faded look consistent with its over-long survival, and hiding paint scheme problems. Here is the car, as I occasionally operate it:

These cars, though stand-ins in various senses of the term, do add variety to my various mail and extra passenger trains. As such, they essentially expand my fleet. That was the reason to explore them in the first place.

Tony Thompson