In a prior post, I addressed some of the issues associated with railroad freight cars moving across international borders, specifically the Canadian and Mexican borders of the United States. I was concerned with how such movements would show up on the waybills for those shipments, and the various appearances that those waybills might have (you can read the post here: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2020/10/waybills-part-75-non-us-freight-cars.html ). Now I want to continue with more on the topic.

One aspect of the topic is further variety in waybills. In the previous post, I showed a Canadian shipment of paper, along with a Mexican shipment of kerosene, the latter re-billed at the U.S. border crossing in Nogales, Arizona. Here are a couple more Canadian shipments, which happen to indicate two different locations for the shipment to clear customs.

The Mexican side is not necessarily more complex (I have not endeavored to create a Spanish-language waybill), but there are some interesting variations possible in details. One that is important to keep in mind is that just as foreign-owned freight cars carried cargoes into the U.S. and could return home loaded, American freight cars that had been unloaded abroad could be loaded back to the U.S.

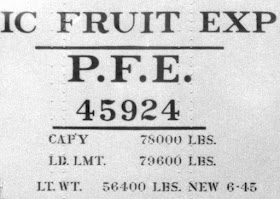

Shown below are a pair of re-billed shipments from the border crossing at Nogales, Arizona, one of which is a Pacific Fruit Express car returning to the U.S. under load. (It’s known that hundreds of carloads of Mexican perishables entered the U.S. at Nogales every year.) The other car, a box car from Ferrocarril del Pacifico, is a model I described last month (see the post at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2020/09/resin-box-car-build-part-3.html ).

I mentioned in the previous post (see first paragraph, at top of this post) that some Mexican railroads provided English-language waybill forms to shippers who wanted to use them. I have not seen one, but decided to make what I thought would be a reasonable facsimile. An example is shown below, again with an American freight car being reloaded back to the U.S. in a T&NO box car.

Perhaps even more interesting is the situation immediately after the sale by SP of its Southern Pacific de Mexico subsidiary to the Mexican government in December, 1951, becoming the Ferrocarril del Pacifico. (FCP). If English-language FCP waybills had not been available immediately, the simplest solution would be to use an existing English-language SPdeM waybill, and type over the road name (there are lots of examples of this kind of thing being done in U.S.).

Then you might produce a waybill something like this one. It’s known, by the way, that the smelter at Cananea produced both sulfuric acid and muriatic acid as by-products, though I don’t know if any of it was shipped to the U.S.

The tank car in question, GATX 64674, was in fact a lease to Mexico national petroleum company Petroleos Mexicano (Pemex), and was so decorated by Tangent Scale Models in their release of this acid tank car model. I did have to declare a modest time warp to use this later paint scheme on my 1953 layout.

Incidentally, for anyone wishing to know more about the Southern Pacific of Mexico, a fascinating railroad looking much like a time-machine reversion to an earlier day on the SP, I highly recommend the book by John R. Signor and John A. Kirchner, The Southern Pacific of Mexico and the West Coast Route (Golden West Books, San Marino, CA, 1987). Copies are readily available on-line, but don’t be sucked in with prices over $100. Be patient, Prices of $50 to $70 often appear, probably less than the book would cost if it were new.

There are some additional matters arising from this topic of cross-border freight car movement, and I will return to the topic in future posts.

Tony Thompson