Many model railroad authors, including me, have long used and advocated use of artist’s colored pencils for a variety of modeling tasks. In this post I want to provide some specifics.

First, brand names. There are numerous brands in any art store, from Neocolor, Polycolor, and others, to the brand I and others have consistently found best, Prismacolor. Prices also vary; Prismacolor is around the middle of the range of prices. I personally think buying something like this purely on price is very false economy, but that is your call. Some pencil brands are very hard and difficult to use for modeling; others, sometimes called “watercolor”pencils, are very soft and again, not as easy to use effectively. But I should hasten to say, if you don’t find that Priamacolor pencils suit you, try other brands until you find what you like.

Small comment on buying these: a small art store, or any store with limited amounts of art supplies, may offer these colored pencils only in sets. The same goes for at least some internet sellers. These sets are not only pricey but naturally contain lots of colors you can’t use. Find a good art store, including chains like Michael’s or Blick. They will have these pencils in bulk and you can choose exactly what you want.

My pencils, in a way, fall into two sets. One set is the lighter colors, and these are shown below.

Listed from bottom to top, these are as follows: white, canary yellow, lemon yellow; and a range of grays, warm gray 30%, French gray 30% (two pencils), and warm gray 30%.

The pencils shown above are used for chalk marks (the white, the yellow, and the lighter grays). A gray chalk mark looks like one that is older and has gotten weathered with time. Such marks are common on the prototype. A second use, for the full range of grays, is to represent weathered, exposed wood that will have tones of gray, such as running boards. I prefer a warm gray tone for this (as you can see from the color names), but Prismacolor also has a range of “cool gray” tones if you prefer that.

In the “boxcar red” range, used on the obvious color of freight cars, my set looks like this:

Again, from bottom to top, these are as follows: pale vermilion, henna, chestnut, burnt ochre, sienna brown, chocolate, light umber, terra cotta, and tuscan red. Some these color names do not match traditional oil or acrylic tube colors, but no matter, just think of them as arbitrary designations.

These too can be used for running board variations, and also for wood-sheathed cars or for wood flooring of flat cars or gondolas. An earlier post contains illustrations of using both the grays and the reddish colors to improve running boards (see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2016/01/running-boards-part-2.html ).

It may strike you that the pale vermilion color does not lie in the range of brown and reddish-brown colors of all the other pencils in the photo above. You are right. The pale vermilion, actually, is used for highlighting, along raised edges such as boxcar doors, or superstructure framing, or even individual rivets,I learned this technique from Michael Gross, and it is impressively effective.

When these pencils are used for general overall weathering, as opposed to selective coloring of running boards or other individual boards, you need a way to diffuse and blend each pencil stroke. (The stroke should be made with the side of a pencil point, not the tip, to avoid a stroke that is too narrow and intense). Again as I learned from Michael Gross, an excellent tool for this blending is an old brush, with its remaining bristles cut very short, less than 1/8 inch long. This can be used to scrub and blend your pencil strokes. As an example, the photo below shows an old no. 12 brush, cut down so it can be used as a scrubber. The penny is to show scale.

This introduction should suffice to get started in choosing and using artist’s pencils for your modeling needs. As with many techniques in weathering, you need to try things out, both to get the hang of any particular method and also to find out what works best for your individual style. So get out there and try these pencils!

Tony Thompson

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Friday, December 29, 2017

My new column in Model Railroad Hobbyist

In the January 2018 issue of Model Railroad Hobbyist, due out today but arriving January 1, is the latest (14th) installment of my contributions to the “Getting Real” column series. It’s turned out to be an interesting column because publisher Joe Fugate has rounded up a diverse crew of modelers to write the column in rotation, from Jack Burgess and Mike Rose, to Nick Muff and myself (and previous contributor Marty McGuirk, who is temporarily on hiatus from the column line-up). Like all issues of MRH, you can read it on line or download it, for free, at any time, at their website, www.mrhmag.com , starting January 1.

My topic this time was an updating and extension of previous work published about prototypical waybills, particularly ways to streamline waybill management, thus my sub-title, “Achieving a Balance between Realism and Simplicity.” Many of the topics within this column will be recognized by readers of this blog, though now assembled into one document. Moreover, nearly all photos in the column are brand new, and none of the waybills had been shown before.

I wanted to emphasize two things in this piece: the simplifications achievable with short or “overlay” waybills, and second, a brief discussion of the ideas behind modeling traffic patterns, or if you will, the flow of freight traffic on a layout.

As this column is a kind of “progress report” on my waybill approach, I didn’t repeat earlier descriptions of prototype waybill procedures or contents, or of the method(s) of preparing model waybills. Instead, I included a summary diagram of the waybill arrangement and contents, as shown below. You can click on the image to enlarge it if you wish.

Some things to note about this model waybill: it has a header at top that was taken from from an actual document of the prototype railroad (SP&S), and it includes the AAR code number, 728. (I described these code numbers in a previous blog, which can be found at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2012/08/railway-accounting-code-numbers.html .)

Further on this example waybill, it was part of the AAR waybill standard to provide full routing from origin to destination, with interchange junctions identified, and this waybill contains such a routing. Examination of routing lists in prototype bills shows that there were no standard abbreviations for junction names, and it would appear that individual clerks often had their own personal set of abbreviations. Note also that there are a few hand-written notations on the bill, as were commonly seen on prototype waybills.

I did spend some time in the column explaining my approach to perishable shipping by season, and the part played by my use of overlay waybills, along with the prototype background. In this blog, this topic was discussed here: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2015/09/seasonality-of-crops-and-traffic.html . Finally, the column contains extensive links and citations of published articles, in an extensive bibliography, so readers can access those earlier materials if interested.

I realize, from comments I hear and emails I receive, that many modelers still have a limited grasp of how model layouts can reproduce prototype traffic flow, so I provided an introduction to that topic in this column. I am continuing to develop that topic and will likely put together a new clinic on the subject, and will likewise be adding blog posts on the subject from time to time.

Tony Thompson

My topic this time was an updating and extension of previous work published about prototypical waybills, particularly ways to streamline waybill management, thus my sub-title, “Achieving a Balance between Realism and Simplicity.” Many of the topics within this column will be recognized by readers of this blog, though now assembled into one document. Moreover, nearly all photos in the column are brand new, and none of the waybills had been shown before.

I wanted to emphasize two things in this piece: the simplifications achievable with short or “overlay” waybills, and second, a brief discussion of the ideas behind modeling traffic patterns, or if you will, the flow of freight traffic on a layout.

As this column is a kind of “progress report” on my waybill approach, I didn’t repeat earlier descriptions of prototype waybill procedures or contents, or of the method(s) of preparing model waybills. Instead, I included a summary diagram of the waybill arrangement and contents, as shown below. You can click on the image to enlarge it if you wish.

Some things to note about this model waybill: it has a header at top that was taken from from an actual document of the prototype railroad (SP&S), and it includes the AAR code number, 728. (I described these code numbers in a previous blog, which can be found at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2012/08/railway-accounting-code-numbers.html .)

Further on this example waybill, it was part of the AAR waybill standard to provide full routing from origin to destination, with interchange junctions identified, and this waybill contains such a routing. Examination of routing lists in prototype bills shows that there were no standard abbreviations for junction names, and it would appear that individual clerks often had their own personal set of abbreviations. Note also that there are a few hand-written notations on the bill, as were commonly seen on prototype waybills.

I did spend some time in the column explaining my approach to perishable shipping by season, and the part played by my use of overlay waybills, along with the prototype background. In this blog, this topic was discussed here: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2015/09/seasonality-of-crops-and-traffic.html . Finally, the column contains extensive links and citations of published articles, in an extensive bibliography, so readers can access those earlier materials if interested.

I realize, from comments I hear and emails I receive, that many modelers still have a limited grasp of how model layouts can reproduce prototype traffic flow, so I provided an introduction to that topic in this column. I am continuing to develop that topic and will likely put together a new clinic on the subject, and will likewise be adding blog posts on the subject from time to time.

Tony Thompson

Tuesday, December 26, 2017

Auto industry traffic, Part 3: prototype equipment

In my first post on this topic, I attempted to summarize briefly what automobile industry traffic is, and how it operated in California, which I model (that post can be found at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/understanding-auto-industry-traffic.html ). I followed that post with a second one, entirely concerned with waybills for such traffic, and accordingly it was made part of my “Waybill” post series, though equally Part 2 of the present series (read it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/waybills-part-61-auto-industry-traffic.html ). Today I am wriing about equipment the prototype used for this traffic.

Let me begin with the term “automobile car.” In the early 1920s, the ARA began to identify box cars with end doors or wide side doors, for loading of bulky cargoes including autos, as “automobile” cars, though it was not required to so letter such cars. Eventually any cars with double doors, or even one-and-a-half doors, were regarded as automobile cars, and were so lettered by most railroads, whether or not they were actually being used to haul automobiles or auto parts. Modelers sometimes think that all cars lettered “automobile” are in auto industry service, or that all cars not lettered “automobile” must not be in auto industry service. Neither statement is true.

In the earliest days of auto transport in box cars, the automobiles were built as a few large assemblies, which could be moved to the loading dock as autos, disassembled for loading into box cars, and then easily reassembled at destination. But as autos grew more complex, this was less practical, and putting two cars on their wheels in a box car wasted a lot of space under the roof.

Shipping complete autos quickly involved wood stands, called “hurdles,” so that the first two autos into the box car could be raised up an angle, and one or two more autos added underneath. In the middle 1920s, the Evans steel auto rack was invented, complete with small chain hoist for raising up the first autos loaded. Shown below is a photo of one of these racks in the “loaded” position, though without an auto in the raised part (Mt. Vernon Car Manufacturing Co. photo).

When a car with such racks was loaded, you could see the racks and also the upper and lower autos, as shown in the photo below (from my collection), of a workman shutting the car door.

The usual design included floor tubes, in which tie-down chains could be stored when the car did not contain automobiles. A rack like this could be folded up against the car roof and secured in place, making the car available for general merchandise loading. Such cars were classified by the AAR as Class XMR, meaning a car with auto Racks, but also usable for Merchandise. If the racks could not be folded entirely out of the way, the class was XAR, meaning a car mainly suitable for auto shipping. The presence of racks was indicated by a 3-inch white stripe on the right-hand door.

Note under the stripe, the lettering which reads “8-D” (you can click to enlarge). This means the rack is an Evans Type D, and there are 8 floor tubes. The car is an SP Class A-50-12 car, photographed by Chet McCoid at Los Angeles in March 1957 (Bob’s Photo collection, used with permission).

Shipment of auto parts was quite different. In general, cars in parts service did not have the word “automobile” on their sides, unless they were double-door cars (many were not). By the 1950s, when I model, the automobile companies had evolved a system of shipping auto components in special-built racks. These racks not only held the parts securely for shipping, but were readily handled by fork lift trucks. Cars were usually modified inside with special hardware on the walls, into which each rack could be keyed and locked for shipment. Naturally each kind of auto part had a different rack (think, for example of what racks might be like for fenders; engines; or transmissions, each with its own distinctive shape and weight).

Shown at left below is one particular rack, this one for automobile axles (such racks might be different in different model years, as auto designs were modified, and of course for different car models in any one year). Shown at the right is the interior of an SP Class B-50-22 box car with custom attachment hardware for a particular rack type (both, Southern Pacific photos). It can be appreciated that a car modified in such a way could no longer serve in general merchandise service. Its AAR class would change from XM to (usually) XAP, for Auto Parts.

For an example of a quite different rack, the photo below shows a stackable Buick engine rack. These were set side by side in the railcar, and being so heavy, would be stacked only two racks high. Then lighter parts, such as gas tanks, exhaust pipes, or other comparable items could be stacked on top. (Photo from Paragon Construction Co., which built many, many racks for SP.) As mentioned in Part 1 of this thread (link at top of this post), racks were built for and owned by the owner of the railroad car, and often scrapped at the end of a model year. Auto parts were a very lucrative traffic

It is probably obvious, but an XAP car, with its specialized rack attachment hardware, would have to return to source empty (but of course carrying its empty racks), and moreover would return to the same plant that was producing its cargo. By contrast, an XMR car could in principle be loaded with merchandise on its return trip. and also could accommodate more than one model of automobile. But as auto parts pools became more formal, and the auto industry tried harder and harder for “just in time” arrivals of auto parts at assembly plants, and also timely shipping of set-up autos, nearly all cars in auto parts and set-up auto service, became “tied” cars that were not used for anything else.

I should mention that this brief overview of auto industry shipping is a topic that is much more extensively discussed in my volumes 3 and 4 of the series, Southern Pacific Freight Cars, as I mentioned in Part 1 of this thread (link at the top of this post). In a following post, I will address model freight cars for this kind of traffic.

Tony Thompson

Let me begin with the term “automobile car.” In the early 1920s, the ARA began to identify box cars with end doors or wide side doors, for loading of bulky cargoes including autos, as “automobile” cars, though it was not required to so letter such cars. Eventually any cars with double doors, or even one-and-a-half doors, were regarded as automobile cars, and were so lettered by most railroads, whether or not they were actually being used to haul automobiles or auto parts. Modelers sometimes think that all cars lettered “automobile” are in auto industry service, or that all cars not lettered “automobile” must not be in auto industry service. Neither statement is true.

In the earliest days of auto transport in box cars, the automobiles were built as a few large assemblies, which could be moved to the loading dock as autos, disassembled for loading into box cars, and then easily reassembled at destination. But as autos grew more complex, this was less practical, and putting two cars on their wheels in a box car wasted a lot of space under the roof.

Shipping complete autos quickly involved wood stands, called “hurdles,” so that the first two autos into the box car could be raised up an angle, and one or two more autos added underneath. In the middle 1920s, the Evans steel auto rack was invented, complete with small chain hoist for raising up the first autos loaded. Shown below is a photo of one of these racks in the “loaded” position, though without an auto in the raised part (Mt. Vernon Car Manufacturing Co. photo).

When a car with such racks was loaded, you could see the racks and also the upper and lower autos, as shown in the photo below (from my collection), of a workman shutting the car door.

The usual design included floor tubes, in which tie-down chains could be stored when the car did not contain automobiles. A rack like this could be folded up against the car roof and secured in place, making the car available for general merchandise loading. Such cars were classified by the AAR as Class XMR, meaning a car with auto Racks, but also usable for Merchandise. If the racks could not be folded entirely out of the way, the class was XAR, meaning a car mainly suitable for auto shipping. The presence of racks was indicated by a 3-inch white stripe on the right-hand door.

Note under the stripe, the lettering which reads “8-D” (you can click to enlarge). This means the rack is an Evans Type D, and there are 8 floor tubes. The car is an SP Class A-50-12 car, photographed by Chet McCoid at Los Angeles in March 1957 (Bob’s Photo collection, used with permission).

Shipment of auto parts was quite different. In general, cars in parts service did not have the word “automobile” on their sides, unless they were double-door cars (many were not). By the 1950s, when I model, the automobile companies had evolved a system of shipping auto components in special-built racks. These racks not only held the parts securely for shipping, but were readily handled by fork lift trucks. Cars were usually modified inside with special hardware on the walls, into which each rack could be keyed and locked for shipment. Naturally each kind of auto part had a different rack (think, for example of what racks might be like for fenders; engines; or transmissions, each with its own distinctive shape and weight).

Shown at left below is one particular rack, this one for automobile axles (such racks might be different in different model years, as auto designs were modified, and of course for different car models in any one year). Shown at the right is the interior of an SP Class B-50-22 box car with custom attachment hardware for a particular rack type (both, Southern Pacific photos). It can be appreciated that a car modified in such a way could no longer serve in general merchandise service. Its AAR class would change from XM to (usually) XAP, for Auto Parts.

For an example of a quite different rack, the photo below shows a stackable Buick engine rack. These were set side by side in the railcar, and being so heavy, would be stacked only two racks high. Then lighter parts, such as gas tanks, exhaust pipes, or other comparable items could be stacked on top. (Photo from Paragon Construction Co., which built many, many racks for SP.) As mentioned in Part 1 of this thread (link at top of this post), racks were built for and owned by the owner of the railroad car, and often scrapped at the end of a model year. Auto parts were a very lucrative traffic

It is probably obvious, but an XAP car, with its specialized rack attachment hardware, would have to return to source empty (but of course carrying its empty racks), and moreover would return to the same plant that was producing its cargo. By contrast, an XMR car could in principle be loaded with merchandise on its return trip. and also could accommodate more than one model of automobile. But as auto parts pools became more formal, and the auto industry tried harder and harder for “just in time” arrivals of auto parts at assembly plants, and also timely shipping of set-up autos, nearly all cars in auto parts and set-up auto service, became “tied” cars that were not used for anything else.

I should mention that this brief overview of auto industry shipping is a topic that is much more extensively discussed in my volumes 3 and 4 of the series, Southern Pacific Freight Cars, as I mentioned in Part 1 of this thread (link at the top of this post). In a following post, I will address model freight cars for this kind of traffic.

Tony Thompson

Saturday, December 23, 2017

Fast clocks

Most modelers are familiar with the concept of a fast clock during layout operation. The clock operates faster than normal time, at some ratio to normal time such as 2:1 (twice as fast as normal time rate). The primary reason for this time management business is to compensate for the fact that our layouts are so compressed in space. Two towns that on the prototype are 10 miles apart, and for which the timetable would schedule an interval of perhaps 18 minutes, are really only ten feet apart on the layout, and a locomotive can cover that distance, even at slow speeds, in well under a minute. To avoid model timetables with stations a minute or even seconds apart, the fast clock at least can provide multiple minutes.

Of course, there can be considerable distortions when a fast clock is used. I once operated on a layout which had an 8:1 fast clock. This may have worked well with the timetable for that layout — I don’t recall because I was operating a local — but it was totally confusing for anyone doing any switching. Every couple of minutes in real time is 15 fast-time minutes. When the dispatcher at one point asked me how much time I would need to complete switching in a particular town, I answered that it would take about ten real minutes. I had entirely lost track of the fast-clock minute intervals.

Most modelers are familiar with the old mantra, that switching takes as much time in the model environment as on the prototype, that is, it takes place at 1:1 time. True, we don’t have to set hand brakes or hook up air hoses, but we also have shorter yard tracks or industrial sidings. Accordingly, any job involving much switching gets rapidly more difficult to do in a timely way, as the clock ratio increases. Even 4:1 puts a real crimp in switching problems.

There do exist layouts which don’t have this problem. The justly famous Tehachapi layout of the La Mesa Club in San Diego uses 1:1 time, because the layout is so big that no time acceleration is needed. Another way the restrictions of fast-time can be avoided is to use no clock at all, but instead operate with a line-up. That really only sets a sequence of trains, without requiring adherence to a timetable, and it is a situation which helps to avoid operators rushing to do their particular job. When my layout was in Pittsburgh, PA, I usually operated with a line-up, and it worked well.

Any layout with a lot of switching work to do will tend to have a relatively slow time ratio for the fast clock (if any). I was intrigued when I visited Jack Ozanich’s Atlantic Great Eastern layout (see my brief account at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/layouts-at-great-lakes-getaway-part-2.html ), when Jack explained that he had found 2:1 to be too fast, but 1:1 a little too slow. He had experimented with intermediate rates, and told us that his current fast clock runs at about 1.7:1. To me this is an interesting example of finding out what works best, even if it isn’t a ratio of integers.

Operation on my own layout is very much dominated by switching. That of course means that any fast clock, if used, would not run at a very high ratio. So do I need one at all? In terms of the switching work, not really, and in fact operating sessions have generally not had any time environment at all. But operation of through trains (as I described elsewhere; see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-role-of-mainline-trains-on-branch.html ). offers the opportunity to tie the layout operation to the prototype Coast Route schedule. That way, a freight such as no. 914 (shown below) can operate on time, and the crew switching at Shumala will have to clear the main line at the scheduled time of this train’s arrival. They know this from consulting the timetable.

With all these considerations in mind, I decided that a fast clock could indeed serve a purpose on my layout. Whether it runs at 1:1 or 2:1 will be decided by experience. Now of course you can immediately question why I want a fast clock to operate at 1:1 — why not just use your wristwatch? The answer is simple. If my operating session is from, say 1 PM to 4 PM, but I want to use the time span in the prototype timetable for the morning hours, I have to ask crews to mentally subtract, say, four hours from the actual time on their watch. I think it might be better to have the “fast” clock, even though running at 1:1, so as to be able to show morning times during an afternoon session.

There are also smart phone apps which can do fast clock ratios, but that assumes that all operators with have such a phone with them and will have the app. In addition, for a 1953 layout, I don’t particularly want people peering at their smart phones. This might be called “breaking the spell” <grin>. Lastly, throttles such as my NCE system can display whatever time you want, right on the throttle, but again, this does not seem “period appropriate” to me.

With all these considerations, I decided to purchase a fast clock. I immediately recognized that for my 1953 layout era, only an analog clock would look right; digital clock displays were many years in the future in 1953. I gave some thought to just buying a conventional analog clock, and simply setting it to the desired starting time for each session. But I do want to experiment with faster time ratios, such as 2:1, and that does take a fast clock.

After asking some fellow modelers for suggestions, and scouting the internet for providers of such clocks, I decided that I like the GML Enterprises offering. You can browse it yourself at their web site, at: http://www.thegmlenterprises.com/id19.html . When I get that far, the installation and use of this clock will be described in future posts.

Tony Thompson

Of course, there can be considerable distortions when a fast clock is used. I once operated on a layout which had an 8:1 fast clock. This may have worked well with the timetable for that layout — I don’t recall because I was operating a local — but it was totally confusing for anyone doing any switching. Every couple of minutes in real time is 15 fast-time minutes. When the dispatcher at one point asked me how much time I would need to complete switching in a particular town, I answered that it would take about ten real minutes. I had entirely lost track of the fast-clock minute intervals.

Most modelers are familiar with the old mantra, that switching takes as much time in the model environment as on the prototype, that is, it takes place at 1:1 time. True, we don’t have to set hand brakes or hook up air hoses, but we also have shorter yard tracks or industrial sidings. Accordingly, any job involving much switching gets rapidly more difficult to do in a timely way, as the clock ratio increases. Even 4:1 puts a real crimp in switching problems.

There do exist layouts which don’t have this problem. The justly famous Tehachapi layout of the La Mesa Club in San Diego uses 1:1 time, because the layout is so big that no time acceleration is needed. Another way the restrictions of fast-time can be avoided is to use no clock at all, but instead operate with a line-up. That really only sets a sequence of trains, without requiring adherence to a timetable, and it is a situation which helps to avoid operators rushing to do their particular job. When my layout was in Pittsburgh, PA, I usually operated with a line-up, and it worked well.

Any layout with a lot of switching work to do will tend to have a relatively slow time ratio for the fast clock (if any). I was intrigued when I visited Jack Ozanich’s Atlantic Great Eastern layout (see my brief account at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/layouts-at-great-lakes-getaway-part-2.html ), when Jack explained that he had found 2:1 to be too fast, but 1:1 a little too slow. He had experimented with intermediate rates, and told us that his current fast clock runs at about 1.7:1. To me this is an interesting example of finding out what works best, even if it isn’t a ratio of integers.

Operation on my own layout is very much dominated by switching. That of course means that any fast clock, if used, would not run at a very high ratio. So do I need one at all? In terms of the switching work, not really, and in fact operating sessions have generally not had any time environment at all. But operation of through trains (as I described elsewhere; see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-role-of-mainline-trains-on-branch.html ). offers the opportunity to tie the layout operation to the prototype Coast Route schedule. That way, a freight such as no. 914 (shown below) can operate on time, and the crew switching at Shumala will have to clear the main line at the scheduled time of this train’s arrival. They know this from consulting the timetable.

With all these considerations in mind, I decided that a fast clock could indeed serve a purpose on my layout. Whether it runs at 1:1 or 2:1 will be decided by experience. Now of course you can immediately question why I want a fast clock to operate at 1:1 — why not just use your wristwatch? The answer is simple. If my operating session is from, say 1 PM to 4 PM, but I want to use the time span in the prototype timetable for the morning hours, I have to ask crews to mentally subtract, say, four hours from the actual time on their watch. I think it might be better to have the “fast” clock, even though running at 1:1, so as to be able to show morning times during an afternoon session.

There are also smart phone apps which can do fast clock ratios, but that assumes that all operators with have such a phone with them and will have the app. In addition, for a 1953 layout, I don’t particularly want people peering at their smart phones. This might be called “breaking the spell” <grin>. Lastly, throttles such as my NCE system can display whatever time you want, right on the throttle, but again, this does not seem “period appropriate” to me.

With all these considerations, I decided to purchase a fast clock. I immediately recognized that for my 1953 layout era, only an analog clock would look right; digital clock displays were many years in the future in 1953. I gave some thought to just buying a conventional analog clock, and simply setting it to the desired starting time for each session. But I do want to experiment with faster time ratios, such as 2:1, and that does take a fast clock.

After asking some fellow modelers for suggestions, and scouting the internet for providers of such clocks, I decided that I like the GML Enterprises offering. You can browse it yourself at their web site, at: http://www.thegmlenterprises.com/id19.html . When I get that far, the installation and use of this clock will be described in future posts.

Tony Thompson

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

Waybills, Part 61: auto industry traffic

In the previous post in this thread, I discussed the topic of understanding rail traffic for the automobile industry. This is just one example of distinctive rail traffic, which might use special equipment, or carry cargo with special needs, or operate in distinctive ways. That discussion can be found at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/understanding-auto-industry-traffic.html . As part of the discussion, I described some helpful sources of information about auto parts in particular.

I have already gotten an email asking why I did not mention the Jeff Wilson book chapter on this topic. The book in question is The Model Railroader’s Guide to Industries Along the Tracks, Kalmbach Books, Waukesha, WI, 2004, and among six industrial summaries it does indeed contain a 9-page chapter on the automotive industry. This book series (eventually there were four volumes, each with six industry chapters) is necessarily brief about most industries, and though I am not aware of any shortcoming in these books as far as accuracy, I will admit I have heard them described as “overviews from 30,000 feet.” That’s a little harsh. First of all, many modelers don’t want a lot of detail, and of course covering six industries in 88 pages per book cannot avoid pretty abbreviated descriptions. But as a starting point for any of the 24 industries in the four books, I would definitely recommend these books. Just don’t look for depth.

In that previous post (cited in the top paragraph above), I showed a Southern Pacific Class B-50-30 box car newly fitted with racks for Buick axles and lettered “return to C&O Ry.” I also showed a table of California auto assembly plants, one of which was the Buick-Oldsmobile-Pontiac plant in South Gate. As I said then, this is already enough information to make up a waybill. Here is an example:

This is only an example bill, because I have not yet completed the B-50-30 kitbash on my workbench; but it illustrates one way to waybill auto parts traffic.

For more about auto parts sources, one can turn to the helpful table in the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force, that I showed in the previous post. This is a terrific resource. It show the company names and locations of a wide variety of parts suppliers, many supplying parts to more than one auto company. Shown below is a waybill made up from information in this table.

Note in both of these waybills that the routing takes the car over the Coast Route. The first one I showed, with the Buick axles, was routed over the Overland Route, as were most auto parts in the early 1950s, and then from the Bay Area to Los Angeles. The second waybill shows a routing via the Cotton Belt and over the Sunset Route to Los Angeles, then up the Coast to Oakland. Might either of these loads have been routed via the San Joaquin Route? Generally, the faster Coast was preferred by SP for hot loads like auto parts.

Lastly, there were also shipments of completed automobiles. The California assembly plants served not only that state but also the rest of the West Coast, along with parts of the Mountain West. In addition, automobile models manufactured in smaller numbers, such as convertibles, might not be assembled in the West, and would have to be shipped to the West from Detroit or other midwestern or eastern plants. This opens up the opportunity for a wide variety of waybills; I will show just one, which is destined to an on-layout team track.

I enjoy learning about different kinds of freight, automobiles and auto parts in this instance, and overview books like the Walthers book are a great help with perspective as wall as specific facts. Through trains on my layout’s SP Coast Route main line now include cars and realistic waybills for different kind of automobile traffic. In a future post I will address the freight cars that are involved.

Tony Thompson

I have already gotten an email asking why I did not mention the Jeff Wilson book chapter on this topic. The book in question is The Model Railroader’s Guide to Industries Along the Tracks, Kalmbach Books, Waukesha, WI, 2004, and among six industrial summaries it does indeed contain a 9-page chapter on the automotive industry. This book series (eventually there were four volumes, each with six industry chapters) is necessarily brief about most industries, and though I am not aware of any shortcoming in these books as far as accuracy, I will admit I have heard them described as “overviews from 30,000 feet.” That’s a little harsh. First of all, many modelers don’t want a lot of detail, and of course covering six industries in 88 pages per book cannot avoid pretty abbreviated descriptions. But as a starting point for any of the 24 industries in the four books, I would definitely recommend these books. Just don’t look for depth.

In that previous post (cited in the top paragraph above), I showed a Southern Pacific Class B-50-30 box car newly fitted with racks for Buick axles and lettered “return to C&O Ry.” I also showed a table of California auto assembly plants, one of which was the Buick-Oldsmobile-Pontiac plant in South Gate. As I said then, this is already enough information to make up a waybill. Here is an example:

For more about auto parts sources, one can turn to the helpful table in the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force, that I showed in the previous post. This is a terrific resource. It show the company names and locations of a wide variety of parts suppliers, many supplying parts to more than one auto company. Shown below is a waybill made up from information in this table.

Note in both of these waybills that the routing takes the car over the Coast Route. The first one I showed, with the Buick axles, was routed over the Overland Route, as were most auto parts in the early 1950s, and then from the Bay Area to Los Angeles. The second waybill shows a routing via the Cotton Belt and over the Sunset Route to Los Angeles, then up the Coast to Oakland. Might either of these loads have been routed via the San Joaquin Route? Generally, the faster Coast was preferred by SP for hot loads like auto parts.

Lastly, there were also shipments of completed automobiles. The California assembly plants served not only that state but also the rest of the West Coast, along with parts of the Mountain West. In addition, automobile models manufactured in smaller numbers, such as convertibles, might not be assembled in the West, and would have to be shipped to the West from Detroit or other midwestern or eastern plants. This opens up the opportunity for a wide variety of waybills; I will show just one, which is destined to an on-layout team track.

I enjoy learning about different kinds of freight, automobiles and auto parts in this instance, and overview books like the Walthers book are a great help with perspective as wall as specific facts. Through trains on my layout’s SP Coast Route main line now include cars and realistic waybills for different kind of automobile traffic. In a future post I will address the freight cars that are involved.

Tony Thompson

Saturday, December 16, 2017

Understanding auto industry traffic

Any layout may have certain kinds of freight traffic that are

distinctive, whether using special equipment, or carrying cargo with

special needs, or operated in distinctive ways. The one I am going to

discuss here is automobile industry traffic, both assembled automobiles

and auto parts, because I know this was a significant traffic component of Southern

Pacific’s Coast Route. But practically any specialized traffic on any

layout could be analyzed in the way I am describing.

I have addressed this topic in a number of previous posts, perhaps most generally in one about the relevant part of my freight car fleet (see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2011/02/choosing-model-car-fleet-4-automobile.html ). I have also summarized prototype SP auto-industry traffic on the Coast Route in a couple of places, most recently at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/09/modeling-freight-traffic-coast-line.html . But in the present post I want to delve further into specifics of the Coast auto parts traffic.

I have relied on three main sources of information for my particular traffic. One is entirely generic and nationwide: the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force (Walthers, Milwaukee, 1998). The book is long out of print at Walthers but is readily available from the usual on-line sellers of used books, such as AbeBooks ( www.abebooks.com ) and on auction sites such as eBay. It’s an excellent overview, both historical and modern. I’ll come back to the contents, but here is the cove:

The book is a full 8.5 x 11 inches in size. It can be criticized as a thinly disguised promo for Walthers structure kits, and that’s true, but it also contains a wealth of information about the auto industry.

The second source is specific SP information that I drew upon in writing certain chapters in my volumes on SP freight cars (series entitled Southern Pacific Freight Cars), the ones about cars in assigned service for automobiles and auto parts. Specifically, these are chapters 6 and 7 in Volume 3, “Automobile Cars and Flat Cars,” Signature Press, 2004; and chapters 8, 11, 12, 13 and 15 in Volume 4, “Box Cars” (revised edition), Signature Press, 2014. These chapters contain numerous details and data about SP assignments for auto parts service. To illustrate with a single example, this photo from Chapter 12 of Vol. 4 (2014 edition) shows a Class B-50-30 car newly equipped with parts racks at the Detroit plant of Paragon, whose logo is at lower right. Note that the racks, purchased by SP to GM specifications, are stenciled “SPCO.”

From SP records. I know this car was in Buick axle service during 1953-54, and the car is lettered next to the door, “return to C&O Ry. Flint, Mich.,” so we know the railroad that served the Buick plant. And there was a Buick-Olds-Pontiac assembly plant in Southern California at the time I model (see the first post cited in the second paragraph in the present post; I will show a more complete list below). As I will show in a following post, this is already enough information to fill out a waybill.

To go beyond the explicit SP information of the kind just shown, one can turn to a helpful table in the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force, on page 56:

This show the company names and locations of a wide variety of parts suppliers, many supplying parts to more than one auto company (you can click to enlarge).

As explained in America’s Driving Force, in the early days Ford was a very integrated company and relied on few outside parts suppliers, while General Motors was almost the opposite,using many of the suppliers listed in the table above, and more. Around 1950, Chrysler was closer to Ford than to GM in its use of parts suppliers, but was changing, as was Ford, toward a wide network of parts companies.

This topic leads me to mention my third source of information, the Internet. As in so many research tasks, Google is your friend. Because auto plants and auto parts companies have employed so many people over the years, and been located in so many communities, the history of these many plants, including an immense list of ones now closed, is readily found on the internet.

Use of the internet information, and tables like the one shown above, give you origins of parts shipments. The other half of the traffic story is the assembly plants, to which the parts moved. Those plants would also be the origin of shipments of assembled automobiles. Two paragraphs above I cited a link to an early list I made of auto plants. Shown below is a more complete list of California assembly plants at the time I model, 1953, and a few added historical details about the plants.

As I stated, these plants are the destinations for my auto parts traffic. (You can click to enlarge,)

One last source of information for an SP modeler of auto traffic: Fred Frailey’s interesting and informative book, Blue Streak Merchandise (Kalmbach Books, Waukesha, WI, 1991). He emphasizes how vital auto parts traffic was to this train by the late 1960s; but in contrast, he lists a train consist of June, 1953 (page 27), with 114 cars, only 13 of which carried auto parts, most for an assembly plant in Dallas. In later years, as SP captured the General Motors parts traffic to their two Southern California plants, an entire section of the BSM was called “Auto Parts West,” all GM parts. This emphasizes that information for your era is vital to understanding this or any particular traffic.

I believe that this description of the information sources for SP Coast Route auto parts traffic provides sound and extensive background. I will go further and show example waybills prepared with this information in a following post. I should add in closing that my focus on the West Coast, and on the early 1950s, is only my own focus. Other eras and other parts of the country can be similarly researched.

Tony Thompson

I have addressed this topic in a number of previous posts, perhaps most generally in one about the relevant part of my freight car fleet (see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2011/02/choosing-model-car-fleet-4-automobile.html ). I have also summarized prototype SP auto-industry traffic on the Coast Route in a couple of places, most recently at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/09/modeling-freight-traffic-coast-line.html . But in the present post I want to delve further into specifics of the Coast auto parts traffic.

I have relied on three main sources of information for my particular traffic. One is entirely generic and nationwide: the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force (Walthers, Milwaukee, 1998). The book is long out of print at Walthers but is readily available from the usual on-line sellers of used books, such as AbeBooks ( www.abebooks.com ) and on auction sites such as eBay. It’s an excellent overview, both historical and modern. I’ll come back to the contents, but here is the cove:

The book is a full 8.5 x 11 inches in size. It can be criticized as a thinly disguised promo for Walthers structure kits, and that’s true, but it also contains a wealth of information about the auto industry.

The second source is specific SP information that I drew upon in writing certain chapters in my volumes on SP freight cars (series entitled Southern Pacific Freight Cars), the ones about cars in assigned service for automobiles and auto parts. Specifically, these are chapters 6 and 7 in Volume 3, “Automobile Cars and Flat Cars,” Signature Press, 2004; and chapters 8, 11, 12, 13 and 15 in Volume 4, “Box Cars” (revised edition), Signature Press, 2014. These chapters contain numerous details and data about SP assignments for auto parts service. To illustrate with a single example, this photo from Chapter 12 of Vol. 4 (2014 edition) shows a Class B-50-30 car newly equipped with parts racks at the Detroit plant of Paragon, whose logo is at lower right. Note that the racks, purchased by SP to GM specifications, are stenciled “SPCO.”

From SP records. I know this car was in Buick axle service during 1953-54, and the car is lettered next to the door, “return to C&O Ry. Flint, Mich.,” so we know the railroad that served the Buick plant. And there was a Buick-Olds-Pontiac assembly plant in Southern California at the time I model (see the first post cited in the second paragraph in the present post; I will show a more complete list below). As I will show in a following post, this is already enough information to fill out a waybill.

To go beyond the explicit SP information of the kind just shown, one can turn to a helpful table in the Walthers book, America’s Driving Force, on page 56:

This show the company names and locations of a wide variety of parts suppliers, many supplying parts to more than one auto company (you can click to enlarge).

As explained in America’s Driving Force, in the early days Ford was a very integrated company and relied on few outside parts suppliers, while General Motors was almost the opposite,using many of the suppliers listed in the table above, and more. Around 1950, Chrysler was closer to Ford than to GM in its use of parts suppliers, but was changing, as was Ford, toward a wide network of parts companies.

This topic leads me to mention my third source of information, the Internet. As in so many research tasks, Google is your friend. Because auto plants and auto parts companies have employed so many people over the years, and been located in so many communities, the history of these many plants, including an immense list of ones now closed, is readily found on the internet.

Use of the internet information, and tables like the one shown above, give you origins of parts shipments. The other half of the traffic story is the assembly plants, to which the parts moved. Those plants would also be the origin of shipments of assembled automobiles. Two paragraphs above I cited a link to an early list I made of auto plants. Shown below is a more complete list of California assembly plants at the time I model, 1953, and a few added historical details about the plants.

As I stated, these plants are the destinations for my auto parts traffic. (You can click to enlarge,)

One last source of information for an SP modeler of auto traffic: Fred Frailey’s interesting and informative book, Blue Streak Merchandise (Kalmbach Books, Waukesha, WI, 1991). He emphasizes how vital auto parts traffic was to this train by the late 1960s; but in contrast, he lists a train consist of June, 1953 (page 27), with 114 cars, only 13 of which carried auto parts, most for an assembly plant in Dallas. In later years, as SP captured the General Motors parts traffic to their two Southern California plants, an entire section of the BSM was called “Auto Parts West,” all GM parts. This emphasizes that information for your era is vital to understanding this or any particular traffic.

I believe that this description of the information sources for SP Coast Route auto parts traffic provides sound and extensive background. I will go further and show example waybills prepared with this information in a following post. I should add in closing that my focus on the West Coast, and on the early 1950s, is only my own focus. Other eras and other parts of the country can be similarly researched.

Tony Thompson

Wednesday, December 13, 2017

Layouts at Great Lakes Getaway, Part 2

I introduced this topic in a previous post, saying a few words about this event, an operating weekend, and describing two layouts, those of Doug Tagsold and Mike Burgett (you can see that post at the following link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/layouts-at-great-lakes-getaway.html ). I visited and operated on more layouts tha those two, however, so this post is to say a little about two others.

The day following my session at Mike Burgett’s C&O (described in the post just cited), I had the distinct privilege to operate on Jack Ozanich’s Atlantic Great Eastern in Battle Creek. Jack’s railroad is freelance, and is set entirely in the state of Maine; it also is set in the season of late winter, when little snow may be seen, but trees are bare and the grass and other ground cover is brownish gray. It is a striking and rarely seen scenic treatment. Jack permits photos, but asks that there be no “aerial”or overall views, only views that could be seen from ground level. Here is such a shot, typical of the main line away from towns.

Some will know that this layout was featured in the 2005 issue of Great Model Railroads, from Kalmbach, with numerous excellent photos.

My job at the AGE was South Dover yardmaster, which had both the good and the bad feature that Jack was serving as the engine terminal hostler there. Good because he was happy to clarify the tasks in my job, and tirelessly answered my questions; but bad because I was right under his eye, and he is, to say the least, a stickler for correct prototype operation. I did make some mistakes in what I was doing, and Jack was quick to point that out, letting me know in no uncertain terms that I was wrong. But I really enjoyed the job, and in a way, having Jack right there was an important part of appreciating the layout for what Jack wants it to be, and how he wants it operated.

The second layout in this group was Bill Neale’s Panhandle Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, set in 1939. I was especially eager to see and operate on Bill’s layout, because his article about his waybill system, published in Model Railroader in February 2009, was what first got me thinking about prototypical waybills. It wasn’t the waybills themselves, which weren’t especially prototypical, but his use of clear plastic sleeves, as used by baseball card collectors, that got me thinking. My first article, about the preliminary version of my own system, then appeared in Railroad Model Craftsman in December 2009. So I wanted to visit the mother ship, so to speak.

Bill’s layout is a superb accomplishment in a 22 x 25-foot room, well described in Great Model Railroads 2010. The job I drew was assistant yardmaster at Weirton Yard, under the direction of yardmaster Henry Freeman. Henry is justly renowned among model railroad operators as a very accomplished yardmaster, so I was in good hands. Here is an overview of the yard.

My job was to help Henry and also switch adjoining industries. One of those was the nearby Weirton Steel plant, and an early task was to pull the empty coal hoppers and take them to the yard. I quickly realized my switcher couldn’t pull them. Henry’s and my engines together succeeded, and to my amazement there were 24 cars out of sight in the plant. (A brief look at the track plan shows that the plant tracks actually connect to a large staging yard!) Later in the session, we delivered 24 coal loads back into the same track in the plant, as you see here, with the plant at left.

Of course the product of the mill is steel, primarily in rolled form, and shipped both as coils and, for thicker sections, as plate. Here is one end of a long string of plate loads in the yaed.

Situated as it is, the layout has locations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, including the Pennsy’s massive bridge over the Ohio River. Bill has modeled a nicely compressed version of that bridge, though I didn’t get a decent photo of it (the Great Model Railroads article has a good view). Bill is also known for his trackwork, sometimes complex, as in this example at Steubenville, Ohio.

I really enjoyed both the Neale and Ozanich layouts, and feel it was a privilege both to see them and to have a chance to operate on them. This operating weekend was well organized and everyone seemed to have fun, as I certainly did. I look forward to returning to GLG in future years.

Tony Thompson

The day following my session at Mike Burgett’s C&O (described in the post just cited), I had the distinct privilege to operate on Jack Ozanich’s Atlantic Great Eastern in Battle Creek. Jack’s railroad is freelance, and is set entirely in the state of Maine; it also is set in the season of late winter, when little snow may be seen, but trees are bare and the grass and other ground cover is brownish gray. It is a striking and rarely seen scenic treatment. Jack permits photos, but asks that there be no “aerial”or overall views, only views that could be seen from ground level. Here is such a shot, typical of the main line away from towns.

Some will know that this layout was featured in the 2005 issue of Great Model Railroads, from Kalmbach, with numerous excellent photos.

My job at the AGE was South Dover yardmaster, which had both the good and the bad feature that Jack was serving as the engine terminal hostler there. Good because he was happy to clarify the tasks in my job, and tirelessly answered my questions; but bad because I was right under his eye, and he is, to say the least, a stickler for correct prototype operation. I did make some mistakes in what I was doing, and Jack was quick to point that out, letting me know in no uncertain terms that I was wrong. But I really enjoyed the job, and in a way, having Jack right there was an important part of appreciating the layout for what Jack wants it to be, and how he wants it operated.

The second layout in this group was Bill Neale’s Panhandle Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, set in 1939. I was especially eager to see and operate on Bill’s layout, because his article about his waybill system, published in Model Railroader in February 2009, was what first got me thinking about prototypical waybills. It wasn’t the waybills themselves, which weren’t especially prototypical, but his use of clear plastic sleeves, as used by baseball card collectors, that got me thinking. My first article, about the preliminary version of my own system, then appeared in Railroad Model Craftsman in December 2009. So I wanted to visit the mother ship, so to speak.

Bill’s layout is a superb accomplishment in a 22 x 25-foot room, well described in Great Model Railroads 2010. The job I drew was assistant yardmaster at Weirton Yard, under the direction of yardmaster Henry Freeman. Henry is justly renowned among model railroad operators as a very accomplished yardmaster, so I was in good hands. Here is an overview of the yard.

My job was to help Henry and also switch adjoining industries. One of those was the nearby Weirton Steel plant, and an early task was to pull the empty coal hoppers and take them to the yard. I quickly realized my switcher couldn’t pull them. Henry’s and my engines together succeeded, and to my amazement there were 24 cars out of sight in the plant. (A brief look at the track plan shows that the plant tracks actually connect to a large staging yard!) Later in the session, we delivered 24 coal loads back into the same track in the plant, as you see here, with the plant at left.

Of course the product of the mill is steel, primarily in rolled form, and shipped both as coils and, for thicker sections, as plate. Here is one end of a long string of plate loads in the yaed.

Situated as it is, the layout has locations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, including the Pennsy’s massive bridge over the Ohio River. Bill has modeled a nicely compressed version of that bridge, though I didn’t get a decent photo of it (the Great Model Railroads article has a good view). Bill is also known for his trackwork, sometimes complex, as in this example at Steubenville, Ohio.

I really enjoyed both the Neale and Ozanich layouts, and feel it was a privilege both to see them and to have a chance to operate on them. This operating weekend was well organized and everyone seemed to have fun, as I certainly did. I look forward to returning to GLG in future years.

Tony Thompson

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Produce shipping boxes, Part 7

In a previous post, I showed one way to make a stack of produce shipping containers, wooden crates in this instance, with customized labels on the box ends (you can see it at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/10/produce-shipping-boxes-part-4.html ). I also mentioned the individual orange crates made by 3-D printing a design of Ken Harstine’s, available from Shapeways. The crates as you receive them are shown below, still attached to the support rods as they were printed. You can see that the two bottom boards are separated slightly to make an opening, and the same is true on the sides of the crates, as was prototypical. An actual orange crate was shown in my third post on this topic (it can be found at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/08/produce-shipping-boxes-part-3.html ).

The crates still being attached to their support makes it easy to paint them. I began by priming with Tamiya Light Gray primer. Then for the “wood” color, I used two different paints. One was Star Brand paint, color no. STR-12, “Natural Wood,” the other was Tamiya XF-59, “Desert Yellow.” These are quite similar colors, the Tamiya perhaps a little lighter and more yellow, but not distinctively so.

In this view, the row at left is the Star color, the row to its right is the Tamiya color. I think both are fine for this application.

At the same time, I built a couple of “box stacks,” representing a stack of shipping boxes in each case, which I could use with printed labels in groups such as 4 boxes wide by 4 boxes high. They were built the same way as the ones described in the previous post that was cited in the first sentence at the top of the present post, using the same Novelty siding. But the present stacks are only one box deep instead of two. As the conventional citrus box is one foot square on the end, I made my styrene “stacks” to multiples of one scale foot. These too were primed with Light Gray, then painted with either the Star Brand or Tamiya wood colors.

Again in this view, the Star color is at left, the Tamiya color at right. The flat area inside the box is simply a piece of styrene to add more gluing surface for the box labels.

Having prepared the box stack parts shown above, I checked them against my label size in HO scale. Unfortunately, they don’t match exactly. It seems to me that in this situation, you have two choices: rebuild your stacks to match the accurately scaled HO labels, or modify the array of labels to have dimensions matching your styrene box stack. It seemed easier to do the latter, at least as an experiment, so I went ahead.

In the photo below, the left stack was mounted with Silver Moon labels (development of that label was shown in my sixth post, which is at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/produce-shipping-boxes-part-6.html ). On the right, the stack has the Summer Girl label, a generic style label, not printed as being for any specific fruit or vegetable, and I chose to modify it for my Guadalupe Fruit Company (see the post at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/produce-shipping-boxes-part-5.html ). Here are both of them.

These box stacks are, as I mentioned, pretty unreadable at HO size. I do like to include them on my loading docks at packing houses, but they are more for flavor than anything else. Here is the stack of “Summer Girl” boxes at Guadalupe Fruit in my layout town of Ballard.

I should perhaps mention that Classic Metal Works offers a stack of boxes that are dimensioned to fit their light-duty trucks, their part no. 20212. These oddly have the side and end appearance out of sync with the top surface, that is, the box size would be different on top vs. sides and ends, but maybe the manufacturer hoped that that won’t be noticed. These too can have custom labels pasted to them, but after experimenting I decided not to pursue this approach.

I like the overall look of these stacks of boxes and will be pleased to have them on my loading docks (subject to the “flavor” comment made above), but frankly I doubt most shippers would have put lots of produce out on the dock until empty cars arrived. I will probably use them sparingly on the layout.

Tony Thompson

The crates still being attached to their support makes it easy to paint them. I began by priming with Tamiya Light Gray primer. Then for the “wood” color, I used two different paints. One was Star Brand paint, color no. STR-12, “Natural Wood,” the other was Tamiya XF-59, “Desert Yellow.” These are quite similar colors, the Tamiya perhaps a little lighter and more yellow, but not distinctively so.

In this view, the row at left is the Star color, the row to its right is the Tamiya color. I think both are fine for this application.

At the same time, I built a couple of “box stacks,” representing a stack of shipping boxes in each case, which I could use with printed labels in groups such as 4 boxes wide by 4 boxes high. They were built the same way as the ones described in the previous post that was cited in the first sentence at the top of the present post, using the same Novelty siding. But the present stacks are only one box deep instead of two. As the conventional citrus box is one foot square on the end, I made my styrene “stacks” to multiples of one scale foot. These too were primed with Light Gray, then painted with either the Star Brand or Tamiya wood colors.

Again in this view, the Star color is at left, the Tamiya color at right. The flat area inside the box is simply a piece of styrene to add more gluing surface for the box labels.

Having prepared the box stack parts shown above, I checked them against my label size in HO scale. Unfortunately, they don’t match exactly. It seems to me that in this situation, you have two choices: rebuild your stacks to match the accurately scaled HO labels, or modify the array of labels to have dimensions matching your styrene box stack. It seemed easier to do the latter, at least as an experiment, so I went ahead.

In the photo below, the left stack was mounted with Silver Moon labels (development of that label was shown in my sixth post, which is at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/produce-shipping-boxes-part-6.html ). On the right, the stack has the Summer Girl label, a generic style label, not printed as being for any specific fruit or vegetable, and I chose to modify it for my Guadalupe Fruit Company (see the post at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/produce-shipping-boxes-part-5.html ). Here are both of them.

These box stacks are, as I mentioned, pretty unreadable at HO size. I do like to include them on my loading docks at packing houses, but they are more for flavor than anything else. Here is the stack of “Summer Girl” boxes at Guadalupe Fruit in my layout town of Ballard.

I should perhaps mention that Classic Metal Works offers a stack of boxes that are dimensioned to fit their light-duty trucks, their part no. 20212. These oddly have the side and end appearance out of sync with the top surface, that is, the box size would be different on top vs. sides and ends, but maybe the manufacturer hoped that that won’t be noticed. These too can have custom labels pasted to them, but after experimenting I decided not to pursue this approach.

I like the overall look of these stacks of boxes and will be pleased to have them on my loading docks (subject to the “flavor” comment made above), but frankly I doubt most shippers would have put lots of produce out on the dock until empty cars arrived. I will probably use them sparingly on the layout.

Tony Thompson

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Another year of this blog

This blog was begun with its first post on December 8, 2010, so this post completes seven years of the blog. Because I model Southern Pacific, I entitled the blog “Modeling the SP,” and SP topics continue to form the core of the subject matter. But modeling a particular railroad does not mean modeling nothing else, so many of the not-directly-SP projects that I carry out, all aimed at reproducing some aspect of prototype railroading, also show up on the blog, as I believe they should.

Each year on the anniversary of the blog I have posted a brief summary of results to date, and commented as seems appropriate. Every single anniversary post has exclaimed about the remarkable (to me, anyway) level of interest, as indicated by page views. The Google application I use for this blog, called Blogger, collects and keeps such statistics, and they continue to be interesting.

After the first couple of years, in which page views essentially doubled each year over the previous year’s annual totals, page view numbers naturally flattened out, and annual increases could no longer sustain an annual doubling. But they do continue to show gently increasing numbers of page views each year. After a couple of years, adding about 170,000 page views per year, they jumped last year to above 200,000 annual page views. (I showed the graph Blogger provides, in my anniversary post last year. You can see it at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2016/12/blog-anniversary-post.html .)

This trend is not ending. Early in the morning on July 5 of this year, my blog reached 1,000,000 page views, yet another astonishing (at least to me) milestone. As I write this post, the total page views are over 1,080,000 page views for the seven years. That means that again in the past year, there have been more than 200,000 page views. I certainly never dreamed of such numbers when I started, and even ten percent of that total would have surprised and staggered me. So for loyal readers out there, I do know about your collective support, and I continue to be gratified as well as amazed by it. (Incidentally, I have set Blogger so that it does not count my own page views. Thus the foregoing numbers are all people other than myself.)

Some time back, I added “reference pages” (as the Blogger application calls them) about my weathering process. Links to them can be found at the upper right of the screen, at the top of each blog post. As I hoped, these are receiving numerous page views. I also continue to place documents occasionally on Google Drive, where they are accessible to the entire internet, not just to those who link from this blog. However, some documents seem not to have entered readers’ consciousness, since I often get questions neatly answered by some of those docs. For example, I added a commodity table for tank cars ( http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2015/11/a-tank-car-commodity-table.html ), which shows you which commodities go in which car types, and what kind of placard each requires, but questions to me continue to indicate that this document isn’t much recognized. Nothing for it but to keep mentioning the existence of resources like this.

Though I had not intended it when I began the blog, a lot of the content has proven to be about projects of various kinds on my layout. Although I do model SP, many layout projects are not directly about the railroad, but about my efforts to reproduce the “look and feel” of SP railroading in Central California in 1953. That is how I would look at this photo of the Guadalupe local switching at Shumala:

Realistic operation, following SP practice, is very much part of the goals for this layout, and I continue to work toward improving it.

Every year, this anniversary gives me the opportunity to think, once again, about the goals of the blog, and whether they are being accomplished. I continue to believe I am doing what I set out to do. I simply wanted to pass on methods, ideas, techniques, and prototype information, when these were beyond routine. I saw no point in describing, for example, spiking a length of track, or following kit directions exactly. I intended to reach a little beyond that level.

I have also realized that my posts have another relatively simple component. I can explain it this way. When academics analyze how information is transmitted within and among technical groups. they always discover the presence of individuals who are called “gatekeepers.” Gatekeepers may control access to information, but more importantly, they increase its circulation. What gatekeepers do is notice new information or ideas that may interest someone in their contact group, whether it’s of value ro them personally or not, and they pass the word. That is part of what I hope I am doing, in writing this blog. I intend to keep doing it.

Tony Thompson

Each year on the anniversary of the blog I have posted a brief summary of results to date, and commented as seems appropriate. Every single anniversary post has exclaimed about the remarkable (to me, anyway) level of interest, as indicated by page views. The Google application I use for this blog, called Blogger, collects and keeps such statistics, and they continue to be interesting.

After the first couple of years, in which page views essentially doubled each year over the previous year’s annual totals, page view numbers naturally flattened out, and annual increases could no longer sustain an annual doubling. But they do continue to show gently increasing numbers of page views each year. After a couple of years, adding about 170,000 page views per year, they jumped last year to above 200,000 annual page views. (I showed the graph Blogger provides, in my anniversary post last year. You can see it at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2016/12/blog-anniversary-post.html .)

This trend is not ending. Early in the morning on July 5 of this year, my blog reached 1,000,000 page views, yet another astonishing (at least to me) milestone. As I write this post, the total page views are over 1,080,000 page views for the seven years. That means that again in the past year, there have been more than 200,000 page views. I certainly never dreamed of such numbers when I started, and even ten percent of that total would have surprised and staggered me. So for loyal readers out there, I do know about your collective support, and I continue to be gratified as well as amazed by it. (Incidentally, I have set Blogger so that it does not count my own page views. Thus the foregoing numbers are all people other than myself.)

Some time back, I added “reference pages” (as the Blogger application calls them) about my weathering process. Links to them can be found at the upper right of the screen, at the top of each blog post. As I hoped, these are receiving numerous page views. I also continue to place documents occasionally on Google Drive, where they are accessible to the entire internet, not just to those who link from this blog. However, some documents seem not to have entered readers’ consciousness, since I often get questions neatly answered by some of those docs. For example, I added a commodity table for tank cars ( http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2015/11/a-tank-car-commodity-table.html ), which shows you which commodities go in which car types, and what kind of placard each requires, but questions to me continue to indicate that this document isn’t much recognized. Nothing for it but to keep mentioning the existence of resources like this.

Though I had not intended it when I began the blog, a lot of the content has proven to be about projects of various kinds on my layout. Although I do model SP, many layout projects are not directly about the railroad, but about my efforts to reproduce the “look and feel” of SP railroading in Central California in 1953. That is how I would look at this photo of the Guadalupe local switching at Shumala:

Realistic operation, following SP practice, is very much part of the goals for this layout, and I continue to work toward improving it.

Every year, this anniversary gives me the opportunity to think, once again, about the goals of the blog, and whether they are being accomplished. I continue to believe I am doing what I set out to do. I simply wanted to pass on methods, ideas, techniques, and prototype information, when these were beyond routine. I saw no point in describing, for example, spiking a length of track, or following kit directions exactly. I intended to reach a little beyond that level.

I have also realized that my posts have another relatively simple component. I can explain it this way. When academics analyze how information is transmitted within and among technical groups. they always discover the presence of individuals who are called “gatekeepers.” Gatekeepers may control access to information, but more importantly, they increase its circulation. What gatekeepers do is notice new information or ideas that may interest someone in their contact group, whether it’s of value ro them personally or not, and they pass the word. That is part of what I hope I am doing, in writing this blog. I intend to keep doing it.

Tony Thompson

Monday, December 4, 2017

Operating with “sure spots,” Part 3

A “sure spot” is a specific car location along a siding, or within an industrial plant, at which cars must be spotted. This can range from a particular warehouse door for a particular commodity (whether loading or unloading), to various requirements for specific unloading capabilities, such as tank car top-unloading, or covered hoppers, or even coal hoppers to be spotted above specific pockets on a coal dealer’s coal trestle.

As I’ve pointed out before, these spots are sometimes called out in waybills, particularly when a shipper regularly ships something to the same consignee — they will have communicated about how the cargo needs to be handled at destination. Or the local agent may know what is needed, or the local train crew may already know from experience where certain cars are spotted, or a warehouse foreman may tell the switch crew what is wanted. I’ve discussed these points in Part 2 of this series; you can retrieve it at this link: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/11/more-about-operating-with-sure-spots.html .

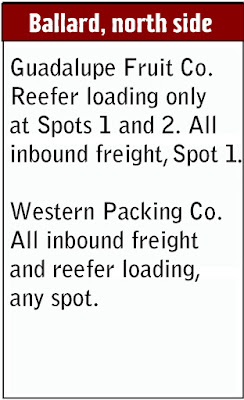

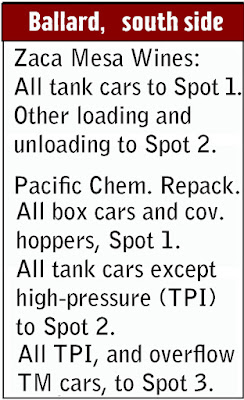

In the present post, I want to expand on the topic I introduced in Part 2 (just cited above), about the use of “information cards” so local train crews know a little of what a prototype crew would know from experience. I have prepared tentative cards for each of the areas where crews may need to have the information, but am not including any maps, because on my layout, crews already have that in their timetable.

I will show just a single map, so that it is clear what is being discussed. This is the same map found in the timetable which crews use, for the town of Ballard. (You can click on it to enlarge.)