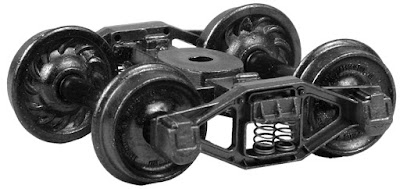

First, the springs. As modelers, we often think of freight car trucks of the 50-ton size as having two springs, which we can see from the outside of a prototype truck. And, after all, model trucks with “working” or “real” springs have just two springs. Here is a representative example of such a “real springs” model truck, which happens to be Kadee but looks like many others of the same type.

To their credit, Kadee is steadily replacing trucks of the above design, with new, solid sideframes.

But real truck springs are not like this. In fact, what looks like one spring nearly always consists of two springs, one inside the other. The photo below (from Union Spring) shows such a pair of springs; note that one is right-handed and one-left handed. There is no way one can see through such springs, as one can do with the model truck shown above.

My late friend Richard Hendrickson experimented with putting a styrene piece behind the springs in “sprung” model trucks, so that you couldn’t see through them, but admitted it was a fussy job. It’s much easier to purchase solid sideframes in the first place. Moreover, one experimenter found that an HO scale freight car had to weigh half a pound before the springs in “sprung” trucks did anything, so they are not contributing to better tracking of any but the heaviest model freight cars.

A further complication in prototype trucks is that a typical 50-ton truck has either four or five springs, not two, and moreover each of them is the kind of pair shown above. Since the 1920s, springs have often been assembled into “spring groups,” as they are called. Here is a Cyclopedia photo clearly showing what a spring group looks like, assembled with spring plates top and bottom, and you can see a spring pair at each corner, and one in the center, five in all. You really can’t see through a group like this.

This happens to be a truck manufactured by Bettendorf, though as many modelers now know, that company ceased production of freight car trucks in 1942, and even when active, produced only a fraction of all freight car trucks. Thus using “Bettendorf” as a generic term for trucks with cast steel sideframes is broadly incorrect, and historically inaccurate after 1942.

By the late 1920s, railroad mechanical people had become aware of the fact that the truck springs then in use gave a relatively hard ride. This was easily improved with longer and softer springs, but then the truck, and the car which rode on it, was prone to harmonic vertical oscillations at certain speeds, leading to severe “bounce” and possible damage to both lading and car. The problem is that a spring readily absorbs energy when compressed, but when the compression force is removed, equally readily releases that energy back in the opposite direction.

This kind of problem with spring behavior had already been recognized and solved with draft gear, where the answer lay in adding mechanical elements which absorbed energy as friction, and then released much less or even none of it, when the original movement force was removed. The same was soon tried with truck springs, in a variety of designs, from practically every company that made truck parts. One easily understood example is the early Simplex design, shown below. Load application was vertical, and the inclined wedge surfaces were the frictional elements. A steel spring is in the center, and transverse springing is accomplished with rubber blocks at each side.

Below is shown one of these Simplex snubbers in place in a 40-ton truck (both photos from PFE).

This general idea, to offer a snubber to the market which could simply be substituted for one truck spring in a spring group, was widely used. Here are two other examples of commercially available snubbers of this type (both photos from the manufacturers). At left is the Miner C-2-XB and at right is the American Steel Foundries (ASF) version of the Simplex design.

Note that a snubber positioned in the center of a spring group, as the Miner is shown above, would be difficult to see in a prototype photo. But often the snubber replaced an outer spring. Shown below is the ASF snubber, installed in a Dalman-Andrews truck (Jack Burgess photo, Richard Hendrickson collection).

For existing trucks, no other method of improving ride was so inexpensive and easy to install.

To my knowledge, we don’t have, in any scale, a model truck with a snubber represented of the kinds shown here, though many thousands of them were sold and installed in the 1930s, and remained in service into the 1950s. But by 1940, a different solution was emerging, and after World War II, would dominate good-riding truck design. I will discuss it in a following post.

Tony Thompson

Fun stuff. A long time ago at the East Bay Model Engineers Society (before they moved to Richmond) we determined that one-piece plastic trucks outperformed sprung trucks, not only because the car weights were not nearly enough to compress the springs, but because sprung trucks tended to twist and parallelogram instead of straying square. My own observation is that we only model empty cars because none of the trucks on our equipment ever show the compressed springs typical of loads! I am tempted to build a model using spring trucks and ACC them with compressed springs....It would lower the car, and I would wind up raising the couplers to compensate...

ReplyDeleteInteresting idea, Dan, but why not just use solid sideframes? Springs look mostly compressed, which is fine for the average model. If one wanted (I have actually had this thought), one could model fully compressed springs on one side of the truck, much less compressed ones on the other side. Then simply reverse the car between loaded and empty moves, as I do with my tank cars and their placards . . .

ReplyDeleteTony Thompson

I've seen the vertical oscillation with Kadee sprung trucks on my "iCar". This car is a kit manufactured by Minuteman Scale Models to carry an iPhone for on-track photography / videography. The iPhone load is heavy enough to partially compress Kadee springs, and in some track conditions, the car will "bounce" - similar to a auto with worn out shocks ("snubbers"), though at a much higher frequency and shorter duration. I continue to use them as they do offer a slightly smoother "view" and compensate for a slight out of squareness of the model between the two trucks.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this post, it clears up some murky understandings of railroad truck springing.

Y cuál es la función de la cuña y el resorte q la comprime

ReplyDeleteThe wedge surfaces provide the friction that dissipates energy. The spring exerts pressure on the wedge to increase the friction.

ReplyDeleteTony Thompson