Last month, I attended the 2022 edition of ProRail, and at one point I was in the hotel bar with several of the attendees. One turned to me, and said something like, “I’ve operated on your layout, and know the layout in more detail than just from a visit, because I read your blog from time to time. But I don’t feel like I understand what you are aiming at.” (There was a ProRail report in a previous post; see it at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2022/05/prorail-2022.html . )

I gave a kind of general answer, but the question wouldn’t go away. So I have reflected further on the subject, and part of my thinking was expressed in the clinic I gave at the Eugene convention of PNR (see my post about the meeting at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2022/05/another-nmra-regional-convention.html ). Entitled “Operating the Santa Rosalia Branch,” the talk went a little ways into my thoughts about goals — in all candor, recognized long after I had implemented them in building the layout.

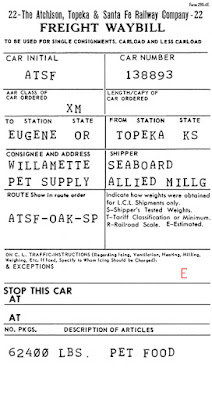

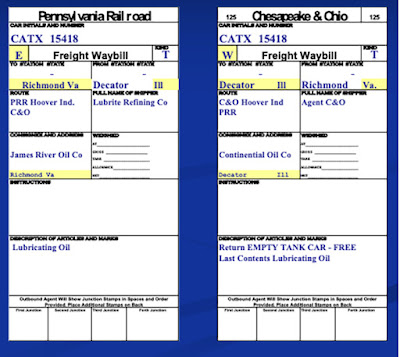

Many of the goals can be heard verbally in my introductory remarks of the YouTube video about my layout, produced by TSG Multimedia (it can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUfmRvun2_w ). There, I explained that my goal was to try and reproduce the work of train crews that did local switching. That means the freight cars and locomotives, reasonable waybills, appropriate other prototype paperwork (see my article in MRH in January 2018, reviewed at: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2017/12/my-new-column-in-model-railroad-hobbyist.html ), and a modicum of knowledge of prototype practice.

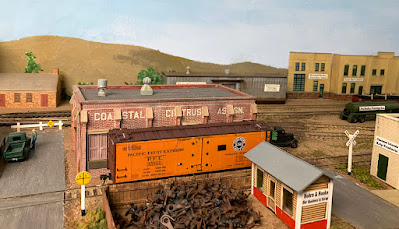

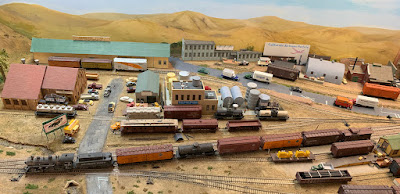

Below is a photo of my layout town of Ballard. I built it over a span of years, always with confidence in what I was doing, but without a clear idea of why I did things the way I did. This post is an effort to clarify what those goals actually are.

Let me start at the beginning. My primary goal is that I wanted to model the Southern Pacific in California, from long familiarity with the railroad and the area. The most interesting part of the SP in California for me was the Coast Division. Second, I knew from the beginning I wanted to model the transition era, because of its interesting mix of motive power.

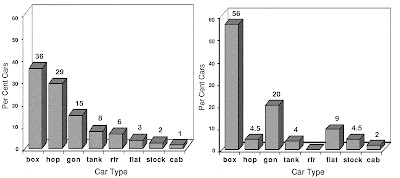

To address the issue of realism of train crews’ work, I wanted my layout freight traffic to realistically mirror the traffic of the SP. That means I had to research the area I would choose to model. There exists a great deal of information about both agricultural and industrial traffic on the SP, so this was a practical goal. Note that this effectively means creating a realistic “beyond the basement” flow of traffic to and from the layout.

Then to be more specific about the layout itself, I knew I wanted a layout that was not too large, to reduce construction demands as well as future maintenance. Second, I wanted my main line to be level, including all staging: no grades. Both these points were lessons learned from my previous layout in Pittsburgh.

Third, I wanted to model a somewhat or entirely rural area, to offer a more spacious feel of towns and to engender agricultural shipping in PFE reefers. I’ve achieved that, with six packing houses on the layout. Below is one of them, the Coastal Citrus Association in my town of Santa Rosalia.

Beyond these specifics, I focused very early on the idea of a branch line. This of course allows fewer large trains (we can rarely operate really prototypical train lengths on transition-era layouts, unless we model branch lines). I chose to model a branch line that never actually existed.

My liking of the “imaginary branch line” stems from my year living in England, where modelers totally embrace this idea (see my post about this: http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2011/04/imaginary-branch-lines.html ). It provides the motive power, cabooses, depots, and much else about a familiar railroad, but in a freelanced area.

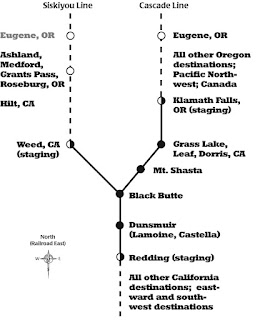

The schematic below, though not very complicated, does clearly show my layout plan, with the two “open” dots indicating locations not modeled. My SP main line is just a loop to and from staging, with the stub-end branch the major modeled area.

I continue to refine my thinking about goals, largely in understanding what I have done rather than what I intend to do. This may seem backwards, but it is what I find interesting at this stage of the layout. I expect I may write additional posts on these topics.

Tony Thompson