I have posted a number of times on the topic for today (if you’re interested, you can readily find those earlier posts by using “standards” as the search term in the search box at right). Usually I mean standards for some particular aspect of modeling, such as trackwork, scenery, weathering of rolling stock, etc. But today, I mean the standard to which we hold commercial models.

The recent Rapido Trains HO scale models of Southern Pacific Class B-50-15 and -16 box cars brought this topic back to my attention. One person, whom I won’t identify, referred to these models as a “flop.” It’s true, the boards on the single-sheathed cars are somewhat too wide, and the Class B-50-16 cars have the bolster (and side post above it) mis-located by 6 scale inches. Does that make the entire production run a “flop?”

Well, of course almost all of us want more accurate models (I’ll comment on what that word really means in a moment). Some readers may remember when Model Die Casting produced a “modern” flat-roof box car, combining elements of at least three different actual box cars. Doubtless this was done so the model would be “generic,” and they could put lots of different paint and lettering schemes on the car; but the model wasn’t accurate for any prototype car.

Now exactly what is an “accurate” model? Does it consist of more than the right length and height and shape of the represented freight car? You might say we can start there. Then, at one extreme, as I showed some time ago for a separate topic (the post is here: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2020/07/waybills-part-72-is-it-merely-visual.html ), you might settle for this:

Of course most of us want more than this, though this item does operate well. And hey, in an operating session, you just move the cars where they’re supposed to go, right? no reason to examine them.

We make lots of compromises already. I can start with the roof of house cars. Our modeling of metal-grid running boards really falls terribly short, despite some lovely products in etched metal (Plano Products and others) and even in styrene (Kadee). But look at this photo (Richard Steinheimer, at San Luis Obispo in 1953; DeGolyer Library, used with permission). I am certain that no one’s model running board looks like this.

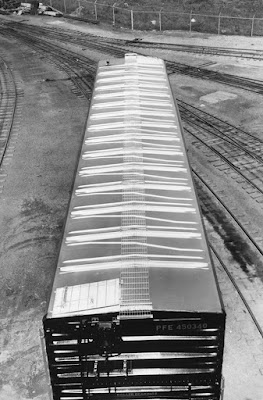

Or let’s look at an entire roof, in this case PFE 450340, Class R-70-13, photographed by Pacific Car & Foundry at their Renton plan). As in the photo above, the ratio of, shall we say, air to iron in this running board is immensely different from the model versions.

So does this mean that every model out there with a representation of a steel-grid running board is a “flop?” No? Why not, if a discrepancy of 6 scale inches makes the Rapido Class B-50-16 a flop?

Of course we can go on to list many, many other compromises in model freight cars. Ladders and grab irons are typically over-thick in commercial models; side doors are often too thick; sill steps are often the wrong shape and size; end corrugations often not really the right shape; and don’t get me started on underbodies and brake gear. Those all gotta be flops, too, right?

Of course, I’m exaggerating to make a point. Every manufacturer tries to do a good job (well, most of them do), and inevitably there are going to be compromises. Hopefully as the years go by, standards increase and we get better and better models (for my modeling era, my freight car examples nowadays, in addition to Kadee, would be Tangent Models and Rapido, and one could add more, especially in locomotives).

Back when I wrote reviews of freight cars and freight car kits for Railroad Model Craftsman, then edited by Bill Schaumburg, he repeatedly reminded me never to say something was “wrong” in a model, but either indicate how it could be fixed, or explain that it was a minor discrepancy. His point? Many less-expert modelers, seeing the word “wrong,” immediately decide not to buy one, and more seriously, tell everyone they know that the model is “wrong” (after all, RMC said so) and no one should buy one.

In directing me this way, Bill was no doubt protecting the tender feelings of manufacturers, to some degree, but he was also making a very important point: keep a sense of perspective. Don’t be one of those people (most of us can name one or two) to whom no error is too small to be blown up into, shall we say, a “federal case.”

Tony Thompson