I was recently reminded of a continuing issue for some layout operating schemes: the cycling of waybills, and whether this is too repetitious. This can be a complex topic. I would like to address several aspects of it, and will begin by providing simple examples of some of my own waybill cycles, to illustrate a few points about which I’m often asked.

(I’ve been writing blog posts on the general topic of waybills for some time, as the series number of the present post indicates. For a guide to the first 100 of these posts, grouped by subject matter, see my post at this link: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2022/11/waybills-part-100-guide.html .)

The most fundamental and, I suppose, obvious cycle is the loaded–empty cycle, whether inbound or outbound as the empty. And the most familiar, I imagine, is the inbound load. Once unloaded, in the typical prototype case, the car is returned to the nearest yard which manages empties via a Car Service office. Such a cycle thus requires two bills, one for the load and one for the empty move.

The example below is a load originating on the Milwaukee Road, as can be noted from the waybill header (you can click on the image to enlarge it if you wish). When empty, we imagine that the Shumala agent has filled out an Empty Car bill to return it to Los Angeles (Taylor Yard), where it will join the pool of empty cars awaiting loading elsewhere, or if not needed, it will return via service route to the railroad which originally delivered it to the SP (the UP at Ogden). This assumes a vigorous economy, in which empties are in demand. (If you wish, you can enlarge these images by clicking on them.)

Note also on the inbound waybill that this is a “milling in transit” cargo. When machining is complete, the outbound movement of the material will also move under that category, allowing a lower tariff rate for the entire sequence (see my previous post on the subject of milling in transit, at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2020/07/waybills-part-71-milling-in-transit.html ).

Of course there are many kinds of such load cycles. To give just one additional example, here is a load inbound to my fish cannery, Martinelli Bros., in Santa Rosalia on the layout, originally loaded on the Northern Pacific. But in this case, because the box car’s owner, the Northwestern Pacific, has a direct connection to SP, the car is routed directly back to NWP. Additionally, we know that NWP requested from time to time that its cars be sent home directly.

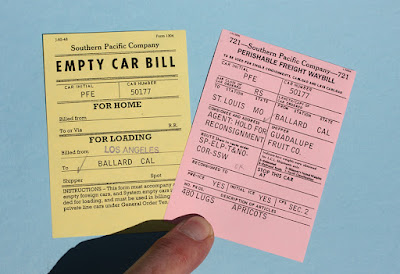

To illustrate inbound empties to be loaded, the Los Angeles Car Distributor received the Ballard agent’s request for an empty reefer, and sent it to the agent for loading (and their office used a rubber stamp to save very repetitious typing). The pink perishable waybill, a color recommended by AAR and followed by SP, shows the outbound cargo and destination, in this case only as far as St. Louis, where the shipper expected to reconsign the load to some other destination..

Tank cars and other privately owned cars were often moved empty on a freight waybill to simplify and speed up movement. Here is an example of a high-pressure car following this pattern. Note that the “shipper” of the empty is the SP agent in town, a common practice for empty movement.

Livestock shipments used a specialized bill, standardized by the AAR, which contained places to note loading time, whether the railroad provided the car’s bedding, and whether the shipper had signed a waiver to permit 36 hours in the car before resting the animals, vs. the standard 28 hours. This is a slightly unusual use by the originating railroad (SP&S) of a foreign-road car, likely reflecting a tight car supply.

All these examples are intended to illustrate prototype procedures. as well as using paperwork reflecting the prototype forms, though considerably simplified for model use. I will return to this topic with additional examples in a future post.

Tony Thompson

No comments:

Post a Comment