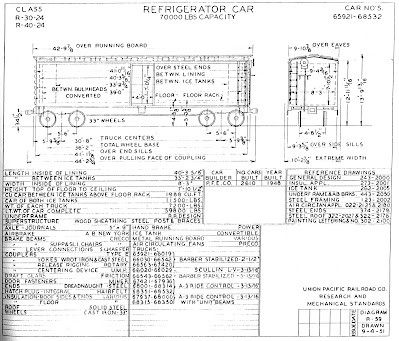

This series of posts describes building a plywood-sheathed refrigerator car, PFE Class R-30-24, from a collection of parts, most of them from Sunshine masters, given to me by Frank Hodina, and the balance provided by Terry Wegmann. Most assembly is now complete; in the previous post (see it at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2022/08/pfe-class-r-30-24-plywood-car-part-4.html ), I showed the assembled and lettered car body with most of its details attached.

Perhaps I should repeat the prototype information: in late 1947, PFE embarked on its last large rebuilding project, converting a few thousand Class R-30-12 and -13 cars (all that remained at that time) to a new class, R-30-24 (or R-40-24, if an occasional R-40-2 car was rebuilt). Notably, these were plywood-sheathed, something PFE had experimented with earlier. For more background and a prototype photo, see the first post in this series: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2020/04/building-pfe-class-r-40-24-car.html .

In the previous post, cited in the top paragraph, above, I mentioned that the model’s car body had been attached to the underbody. That meant it was time to add the corner

sill steps. I used the A-Line “Style A” steps, installed with canopy glue.

These are very similar to the PFE style. Here is the model at this point, with those steps unpainted.

My box of parts

included some super brass parts for the two-rung steps for under the

door. I am not certain who made them originally (I am reliably informed that it was Terry Wegmann), but they

are great looking, have nice attachment pins, and are sturdy.

I attached these steps with canopy glue, along with the fan control boxes on the side sill near the fan shaft hub.

Last, I attached an etched metal running board, and ice hatch latch bars, all with canopy glue. I had to hand-bend roof corner grabs to match the roof mounting holes, for which I used 0.015-inch brass wire, and attached them with canopy glue. As the car photo above is of the left side, I show the right side below.

I could now proceed with weathering. This car would be 5 or more years old by the time I model, in 1953, and it has the original paint scheme that it received when rebuilt. But as experienced modelers know, age alone is not a guide to the state of weathering on PFE cars, becuase they were frequently washed until about 1953 or 1954. Naturally one can only guess how many times a car may have been washed since going into service.

Given that uncertainty, I decided on moderate weathering only. Once the car was weathered and that coat protected by flat finish, I added reweigh decals, route cards, and chalk marks. (All those points of detail have been covered in prior posts, and you could use any of those terms in the search box at the top right of this post to find them.)

With that, this car was ready to enter service on the layout, and I show it below, spotted at Coastal Citrus, a lemon shipper, in my layout town of Santa Rosalia. You can compare its appearance to the next photo above, which was taken prior to weathering and finishing. PFE orange did indeed fade toward a more yellow color, as I’ve tried to do here.

This was a fun build, one I had been looking forward to, and marks completion of one of the two plywood car projects on my bench. Still working through the stash, in a sense.

Tony Thompson